I have spent most of my career measuring go-to-market effectiveness across many different industries. I find myself increasingly thinking about what I’ve learned—not about the techniques of measurement, but about the right investment decisions in various scenarios. Because I’ve been inside at least 100 brands’ data, I have quite a few heuristic learnings about what to do, and when. I thought I’d put them down on paper.

The Discriminatory Dimensions that Matter

Like any good consultant, I look for organizing frameworks to help make decisions. I came up with five dimensions that seem to drive choice in marketing mix. This is a blog post so they may change, but I believe them to be mostly exclusive, and maybe 80% exhaustive. So, mEcE?

- Transaction Complexity: How many forms, sign-offs, and configuration steps are required to purchase the product? In other words, how much “buying friction” is involved? Examples of complex transactions include buying a car, configuring a new software license, or opening a bank account. Examples of simple transactions include buying a can of soda or a media subscription. I originally had “criticality” as a separate dimension—whether the purchase could potentially drive a lot of buyer’s remorse, but upon further reflection, I think it’s almost perfectly correlated with transaction complexity.

- Competitive Landscape: How many competitors are there, what is their market share, and what are they spending on marketing? A highly competitive market tends to be well-defined and attractive, whereas less competitive markets are more niche, or have high barriers to entry. Examples of competitive markets include airlines, consumer package goods, and consumer banking. Less competitive markets include niche B2B or software plays and essential monopolies like utilities. New entrants to competitive markets generally have a very steep hill to climb when it comes to marketing investment.

- Distribution Strategy: Is the product being sold directly, through third parties, or both? Companies selling their products directly have an information advantage: They know their customers and can see them progress through the shopping process—whether via e-commerce or via sales reps entering information in a CRM system. Selling via partners or retail trades distribution scale for information and margin.

- Wanted vs. Needed: Is the product a desired purchase or a necessity? Just like the Rolling Stones song, keeping oneself fed, clothed, and housed are needs for pretty much everyone. These critical needs can be driven by emotion, but quality, price, and circumstances tend to trump. Luxury goods and impulse purchases are far more about scratching an itch or signaling to others and require very different marketing approaches.

- Product Lifecycle Stage: Is this a new category, or established? New categories require education and evangelism. There’s evidence that “First Mover Advantage” is a myth; the first movers soften up the market for later entrants who don’t need to spend as much on go-to-market.

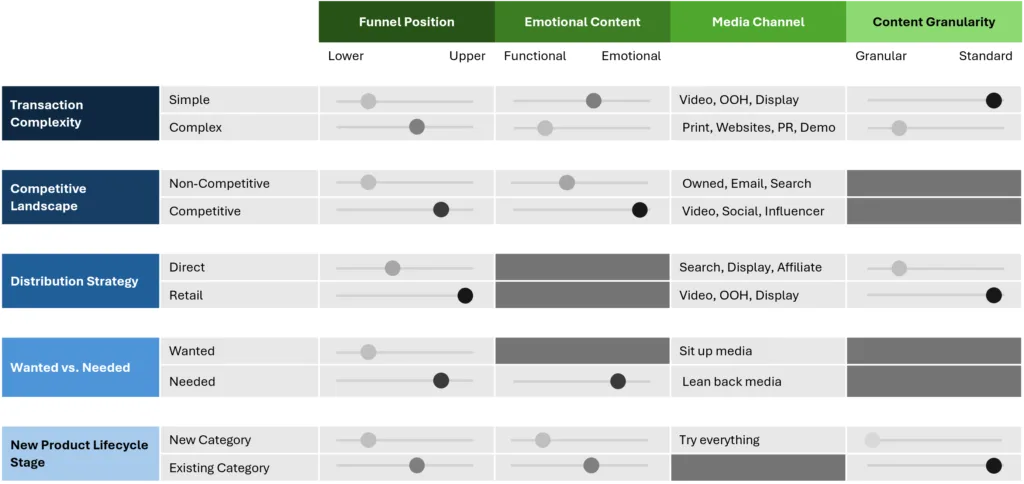

Figure 1: The five product dimensions that matter when choosing a marketing mix.

The Decisions that Matter

Just like there are discriminatory dimensions, there are dimensions of decision-making around marketing. Oftentimes, marketers will use the term “channel” as a catch-all, particularly in media mix modeling. However, this is doing the richness of media planning a disservice. Each channel is really a collection of attributes. While channels certainly have their own unique dynamics, how to employ multi-channel strategies with these other marketing dimensions is where organizations can differentiate themselves.

- Funnel Position: Upper-funnel advertising drives awareness or affinity; mid-funnel advertising typically serves to educate; and lower-funnel advertising converts ready-to-buy customers. Upper-funnel advertising can be thought of as a “TAM (Total Addressable Market) Booster.”

- Emotional Content: Emotional messaging (sometimes called “System One”-type messaging, after Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast, Thinking Slow framework) drives brand equity—that ephemeral store of goodwill in consumers’ brains that takes years to build—and can last for decades. Functional messaging (System Two) acts quickly, typically reminding customers of a product with rational price-value proposition and a buying opportunity.

- Media Channel: Media channels are incredibly diverse, and getting richer. Thirty years ago, we would talk about print, TV, out-of-home, and mail. Today, we have social, streaming video, display, search, affiliates, influencer, gaming, and mobile—to name only a few. To make it more complicated, each publisher within a channel has their own unique blend of audience, medium, content, addressability, and measurability. All this being said, “Linear TV,” for example, does have immutable traits that are different from streaming video, and publishers within media channels tend to have much in common—including transaction economics.

- Content Granularity: Content can be customized to finer and finer degrees, to match audience affinity, test concepts, or both. The term for this used to be “one-to-one marketing”; in B2B settings we call it “account-based marketing.” The promise of purpose-built content for specific audiences is obvious; if we know exactly what Jane wants to see or hear, and can provide that, we’ll perform better, all else being equal. However, while tempting, content “small ball” can be difficult to execute and measure.

Figure 2: The four marketing mix decisions that matter.

What to Do, All Else Being Equal, for Each Dimension

Every marketing mix decision is complex, but there are some established “laws of physics” that apply in each discriminatory dimension. It’s surprising how often these are ignored by marketers.

Transaction Complexity

High transaction complexity products require education and longer sales cycles. Because they tend to be “high consequence”—said another way, if the buyer makes the wrong choice, they will have a lot of remorse—buyers need to be reassured emotionally and functionally.

Full-funnel marketing is certainly required, but upper-funnel activities should focus on quality and eliminating barriers to purchase. Self-service educational content should be easy to find, with links from upper-funnel digital media to that content. Pushing buyers to buy too quickly can be counterproductive.

Content should generally be less emotional for high-complexity products. Because complex products require “thinking slow”—rational decision-making—focusing too much on pathos can be off-putting for consumers. Creating a feeling of safety should be the goal—ensuring that buyers will be taken care of post-purchase.

High complexity products can also take advantage of more content granularity, both because higher transaction sizes make customization economically feasible, and because there tend to be very real differences between buying use cases. That being said, more content does not always equal better outcomes. In A/B tests over the years, we have consistently found it difficult to beat a “generic” best message with tailored content, perhaps because targeting the right audience for content remains challenging.

For simpler products, the opposite strategies tend to apply. Simpler products still require full-funnel marketing, but upper-funnel tactics should focus on emotional resonance (System 1-type thinking.) Content should also be less granular, and focused on simple, universal messages.

Competitive Landscape

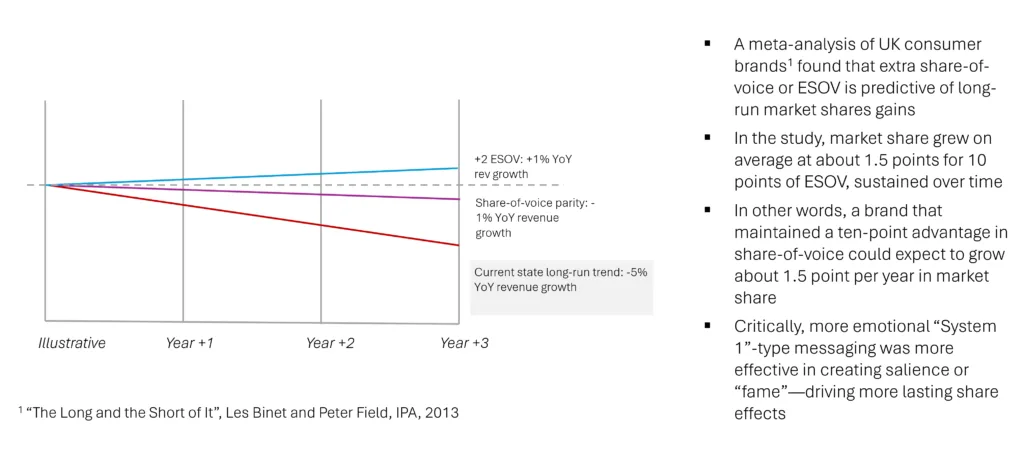

Competitive product landscapes require competing on share-of-voice. This has been well established, in studies such as Binet and Field’s The Long and Short of It. The essential message is that brands that want to grow market share need to advertise above their “fair share”—a higher share of voice than market share. As shown in Figure 3 below, a ten-point extra share of voice position (e.g., 50% SOV vs. 40% market share) will drive about 1.5 percentage points of share growth per year, if sustained.

Share-of-voice, in this case, means upper funnel, emotional (System One) advertising. This is perhaps the hardest thing for CMOs to do, however, as this type of advertising is the least measurable. This mismatch between the right strategy and measurability might be the number one factor driving CMOs’ notoriously short job tenure.

Figure 3: All things being equal, consumer brands in competitive markets need to spend above their fair share to grow. This spending should be emotional (System One.) Promotions, price, and functional education don’t help much.

This extra share-of-voice can be achieved across many media channels, but video and visual media are better. These types of channels typically meet consumers when they are leaning back and relaxed.

Less competitive, niche markets do not necessarily require competing on share-of-voice and can get by without much upper funnel advertising. Less competitive markets can rotate to lower funnel activities, focusing more on the functional benefits of their product or solution (System Two). However, the total addressable market can be stunted without education outside of prime prospects, so it’s always worth testing additional tactics. Increasing cost-pers and slowing sales are also indicators that the top of the funnel needs to be filled—but don’t wait too long, or you could be fighting an uphill battle

Distribution Strategy

Consumer package goods (CPG) companies have traditionally relied on retailers to transact with consumers. While this model has been challenged over the past decade—think Dollar Shave Club—retailers are still king for smaller transaction-size, simpler products.

This means that CPG companies have always been forced to compete with broad-reach advertising. Affiliate marketing just isn’t attractive for Tide detergent or Coca-Cola; neither is paid search. Instead, brand managers at P&G are trained to think from the consumer’s perspective, building marketing strategies using pro formas, with feedback from econometric (MMM) models. We’ve often said that CPG’s bane (being unable to know their customers directly) is actually a benefit; being information-poor requires better marketing and better thinking.

Direct-to-consumer (DTC) companies have far better data about their prospects and their customers. They invest in software to track them through the buying cycle, and buy (down-funnel) performance media to bring them to their site. This isn’t the wrong strategy; companies with direct relationships should spend far more on down-funnel media. They should also be able to customize in a far more granular way, as they know more about their audiences. However, over-rotating too much towards performance media is a danger.

This devolves, particularly in competitive markets, into companies chasing low value switching customers into each other’s arms—all the while lining the pockets of late-stage goalkeeping media companies, particularly affiliates and paid search.

Wanted vs. Needed

Needed products—water, milk, toilet paper, housing—aren’t particularly sexy on their face. It’s tempting to therefore assume that a more functional marketing approach would be more appropriate. However, this is almost precisely the opposite of what to do.

It’s right there in the name—wanted products are desired. In a sense, the marketing is built into the product; the marketer just needs to provide distribution. Needed products need help to stand out.

Wanted products tend to perform better in down funnel-heavy strategies. Because they are desired, marketing’s goal should be to surface it to as many people as possible and “let it sell itself.”

Needed products depend hugely on brand identity. Building brand identity takes decades of persistence. Upper funnel marketing focused on core brand (emotional) attributes is a key part of building the brand, which will ultimately translate into lower demand price elasticity (pricing power), better shelf placement at retail, and higher, longer-term sales.

Product Lifecycle Stage

Truly new products are unique cases. On the one hand, good product-market fit can create a flywheel that takes off on social media, creating a firestorm of demand. These “lightning in a bottle” scenarios do happen—but they are very hard to predict. It’s more common that new products require evangelism: Spreading the news before competitors catch up.

This is why a good amount of venture capital funding goes towards go-to-market. High initial CPAs (cost per acquisition) are worth it if those users start telling others about the product, and if they stick around for a long time (high customer lifetime value, or CLV).

In a first-mover situation, spending mostly down funnel on performance marketing can make sense—obviously, if there is a solid product-market fit. In this case, down-funnel performance marketing can be very simple; you have a need; we have a product; it’s new. This isn’t emotional or trying to create brand love; it’s informational.

In a competitive new product category, things get squirrely. A common occurrence is that a first mover innovates, and for the first year or few years, thinks things are easy. Profits are high, CPAs are low, and it seems like smooth sailing. However, lucrative markets attract competitors. It can take quarters or years for some first movers to realize that they’re losing share, buried in the noise of weekly lead or sales reports. In these cases, it’s essential to get ahead of competitors and begin upper-funnel advertising before competitors get a foothold. In other words, it’s all about timing.

New product launches also benefit greatly from multi-channel approaches. Testing across different channels will yield a plethora of insights that can be quickly turned around into strategies. New product marketers will learn something new every month—provided they experiment.

The same can be said for content granularity. Most older product categories have settled on the content that works; it’s hard for creatives to break through. Brand-new products can try crazy messaging, and it can work.

Figure 4: “Teddy told me that the most important idea in advertising… is new. Creates an itch…” Maybe so, but you have to watch for the copycats on your heels.1

Summary Cheat Sheet

With all that being said, here’s an attempt at a cheat sheet matching the discriminatory scenario dimensions with marketing decisions. Of course, these are rules of thumb and should be validated via both econometric modeling and continuous testing or either.

Figure 5: All things being equal, start with these strategies depending on the dimensions (blue) of your business problem.

Download our framework, “Measuring Marketing’s Effectiveness”

Access our whitepaper for a deep dive into additional imperatives and methods for CMOs and analytics teams driving measurable marketing ROI.

1 “The Wheel.” Mad Men, created by Matthew Weiner, season 1, episode 13, Lionsgate Television, 2007.